Housing gets an “F” in Vital Signs 2022 report

By Shannon Waters, Capital Daily

There are many things to love about living in Greater Victoria but the housing market is not one of them as the 2022 Vital Signs report illustrates.

More than 2,500 residents completed this year’s survey and gave overall quality of life in the region a B+ grade—citing the natural environment, climate, and parks as the Capital region’s best features—while housing received an F.

Housing has been a weak point for the region since the first Vital Signs report was released in 2013 when respondents gave it a C grade, the lowest of the survey’s 12 categories. The 2020 and 2021 reports saw housing given a D+; this year, 51 per cent of respondents gave the issue an F.

Lack of affordable housing is “an obvious issue” that has been percolating in the region for a long time, says University of Victoria social policy professor Michael Prince.

“That should be a takeaway for municipal leaders—your community has spoken,” Prince told Capital Daily. “There’s no doubt about it. Let’s get going on it and work together.”

Adding affordable homes and more rentals is by far the best way to “make Greater Victoria an even greater place to live,” according to 44 per cent of survey respondents—by far the most popular priority this year.

People who rent their homes reported poorer housing affordability than homeowners with 64 per cent of renters rating the availability of affordable rental homes as “poor” compared to 54 per cent of homeowners. Just 7 per cent of respondents said there are adequate affordable home ownership options in Greater Victoria; less than 4 per cent of renters said the same.

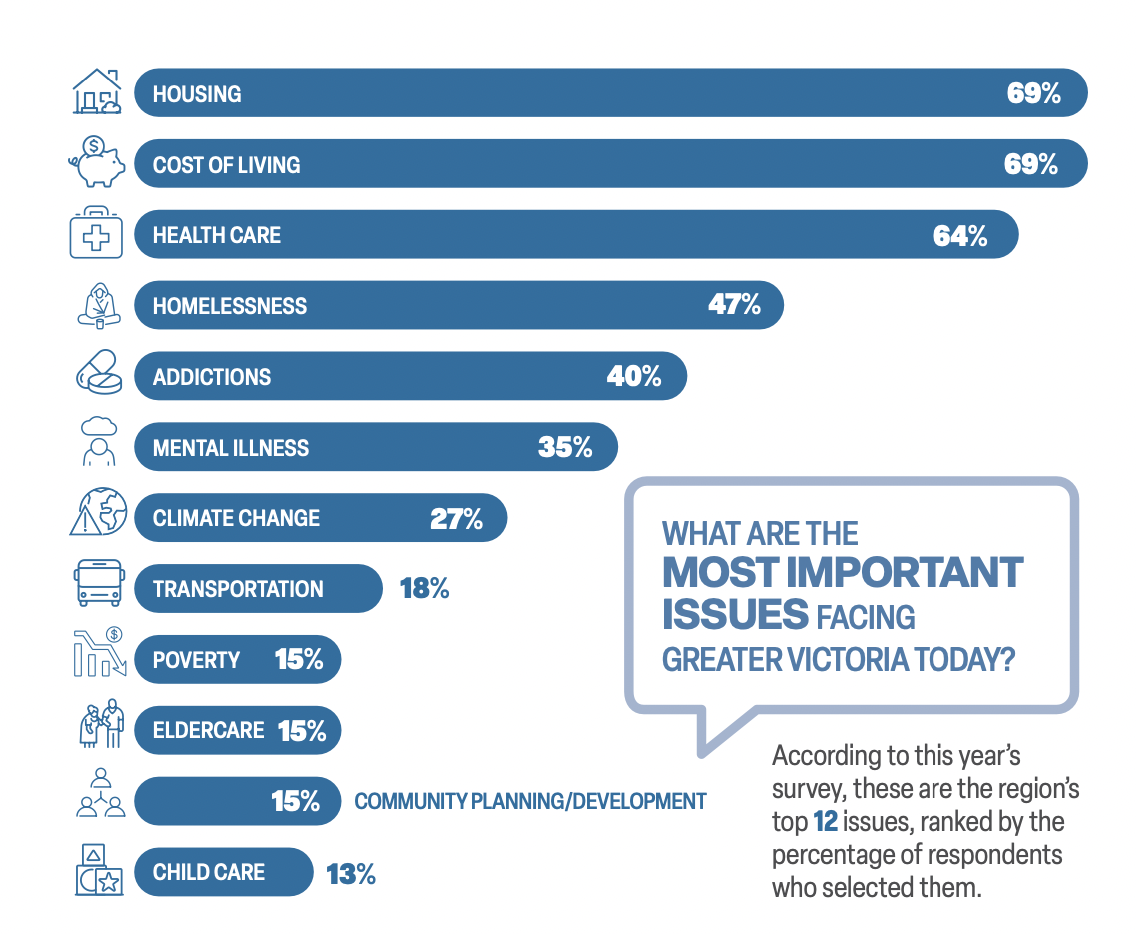

Vital Signs 2022 shows housing and cost of living issues tied as the “most important” issue facing the region with health care close behind and homelessness, addictions, and mental health rounding out the top five.

Satisfaction with standard of living holds steady compared to 2021

Despite the downgrade for housing, this year’s report saw standard of living receive a B-, the same grade received in 2021 and down slightly from 2020’s B-grade. The survey shows satisfaction with Greater Victoria’s standard of living has improved slightly since the pandemic hit; 2019’s standard of living grade was a C+.

That is “a bit of a surprise” to Prince.

“You would have expected to see a pretty dark mood,” he said, speaking of the anticipated impact of COVID with its public health restrictions, social isolation, and negative impacts on many businesses.

Government support programs for both businesses and individuals and the size of public sector employment in the region may have buffered against the worst of the pandemic’s impacts.

“[In] Greater Victoria, we’ve got naval yards, we’ve got a lot of government jobs so a lot of payrolls did hold firm, unlike maybe other towns or cities that are more reliant on [the] service sector [and] small businesses that would have been hit hard,” Prince said.

But with inflation running high and the possibility of a recession looming, Prince sees plenty of uncertainty on the horizon.

“We’re seeing issues around cost of living and affordability and food prices in a way that we haven’t seen in many, many, many years so we’re kind of in uncharted waters,” he said.

The cost of living crunch can already be seen in the 2022 Vital Signs report, according to Diana Gibson, executive director of the Community Social Planning Council. She points out that 47 per cent of respondents rated their income as “Below Average” or “Poor” comparedto the local cost of living.

“That’s almost half of folks that are suffering in terms of their wage relative to inflation,” Gibson said. “I think we’re going to see more of that coming soon.”

Income, of course, makes a significant difference in people’s standard of living. On every question about standard of living in the report, respondents earning $80,000 or more were much more likely to select the “Excellent” rating than those earning less—from their ability to afford necessities (29 per cent vs 9 per cent) to their access to nutritious, culturally appropriate food (32 per cent vs 16 per cent) to their overall quality of life (31 per cent vs. 15 per cent).

The gender gap is still going strong

Gibson also noticed “a gender dimension to how people are reporting they are doing in this economy.” While 13 per cent of men who completed the survey gave their overall standard of living an A grade, only 3 per cent of women said the same. Men were also much more likely to rate their income compared to cost of living as “Excellent” than women were (10 per cent vs. 5 per cent).

“When we see the economy get tighter like this, we do see inequality grow and we see that gender gap grow,” Gibson said. “This really shows that there’s still definitely a demographic gap around standard of living.”

A lack of affordable child care may be part of the equation: 66 per cent of respondents rated access to affordable child care “Below Average” or “Poor.” Again, men were more likely than women to report better situations with 15 per cent saying they have “Good” or “Excellent” access to affordable child care compared to 9 per cent of women.

Gibson was “somewhat surprised” respondents rated affordable child care access so low despite investments by both the provincial and federal governments in recent years.

“It’s just not been enough,” she said, adding that access to affordable child care can take a bite out of cost of living issues.

“In 2019, the living wage went down because of child-care investments,” Gibson said. “You can really see that an investment in something like child care can really address affordability for families.”

In 2021, the living wage for Greater Victoria was $20.46 per hour—a 5.5 per cent increase from 2019 and 23.5 per cent more than BC’s $15.65 minimum wage.